Look at the following extract:

Look at the following extract:

Child: Nobody don’t like me.

Mother: No, say ‘nobody likes me’.

Child: Nobody don’t like me.

(Eight repetitions of this exchange)

Mother: No, now listen carefully; say ‘nobody likes me’.

Child: Oh! Nobody don’t likes me.

(McNeill, 1966)

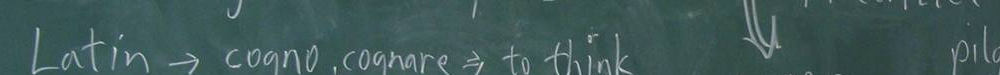

The behaviourist approach to language learning grew out of the belief that students could learn a second language by being taught to produce the correct “response” to the appropriate “stimulus”. The student would then receive either instant positive or instant negative “reinforcement” in the shape of either correction or praise from the teacher.

The resulting methodology, audio-lingualism, was a very heavily teacher-centred approach consisting of a lot of “mimicry and memorization”. The linguist Leonard Bloomfield claimed that “language learning is over-learning” and this, in effect, was what audio-lingualism was based on.

The proponents of the audio-lingualism believed that language learning was a process of habit formation in which the student over-learned carefully sequenced lists of set phrases or “base sentences”. The method was extremely successful and enjoyed considerable popularity.

Good L2 (second language) speaking habits would be reinforced in students and simplistic, predictable, repetitive drills would try and ensure the absence of error. Mistakes were not to be tolerated in audio-lingualism. They only proved the “good” habits hadn’t yet been learnt. The mother/child exchange above shows an attempt by the mother to correct a young L1 (first language/mother tongue) learner without success.

The teaching theories that followed after audio-lingualism (which was especially dominant in the 1940s and 1950s) put higher priority on what the learner was sub-consciously “doing” with the language. These theories suggested that, far from trying to stamp out error and getting children to “mimic” as in this example, the parents would be better off allowing the errors and accepting that the children’s “inter language” is not yet ready for the target structures. The “inter language” is the current system or blueprint of language that exists in the learner’s head, constantly updated and altered as the learner acquires the target language.

In the extract above, the child’s inter-language seems to contain the rule “use of auxiliary verb to form negative” but still lacking that which precludes double negatives. The adult’s “audio lingual” attempts at error correction are clearly in vain.

Pingback: Theories in learning English as a foreign language – julesvocteacher